The Mixed-Media Testimony of Terrence Gore Blooms Inside Bartram’s Historic House

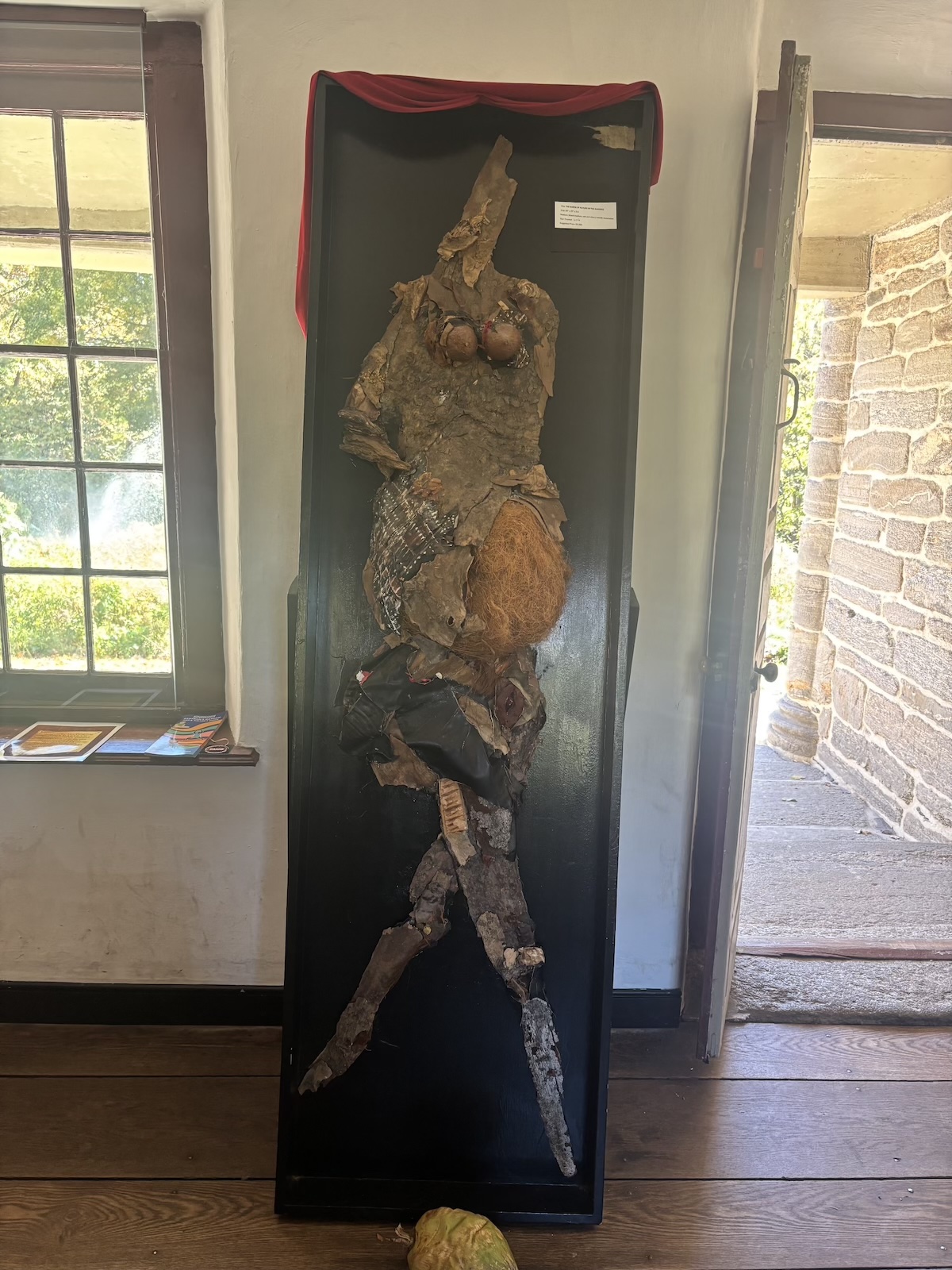

On a gray afternoon at Bartram’s Garden, the historic stone house feels like it is listening. Inside, mixed media works by Terrence Gore line the walls. One long piece, more than six feet of layered color, text, and found materials, stops visitors in their tracks. Some lean in to read fragments. Others step back and simply feel it. More than once, Gore has watched people cry in front of this work.

“This is my creative story of survival,” he says. “I use my art as a teaching tool, telling stories of natural beauty, and as a survival tool, as medicine for the soul.”

Terrence Gore’s exhibition inside the Bartram House, “Back to My Roots,” is a homecoming for a Geechee boy who grew up at the edge of this National Historic Landmark, and a living archive of Black life and memory on what he calls “some of the richest land in Philly.” For Gore, it provides an opportunity for others to experience the Garden as he has known it for over 50 years.

Terrence Gore: From Bartram Village to Bartram House

Gore’s family migrated from Savannah, Georgia, to Philadelphia in 1967, part of the Great Migration that reshaped American cities. In 1971, they moved into Bartram Village, the public housing development beside Bartram’s Garden in Southwest Philadelphia. “I grew up in this park,” he says. “Bartram’s Garden was my backyard, a clothesline, fashion inspiration, and sanctuary green space.”

That landscape had once been shaped by John Bartram, the eighteenth-century botanist and trusted friend of Benjamin Franklin, whose plant collecting, field explorations, and far-reaching scientific correspondence helped establish Bartram’s Garden as the oldest surviving botanical garden in the United States.

Terrence Gore was also drawn to the Bartram House itself. “I was amazed by John Bartram’s house,” he remembers. “We could only visit it from the outside when I was growing up. The architecture was astonishing. I wanted to know what was in such a structure that was so pristine, yet so private to me.”

For decades, he walked the grounds as a neighbor and an unofficial student of the landscape, while the house remained closed to him. Now his work fills its rooms.

“This little boy who was tippy-toeing, trying to look into the window, is now inside the building,” he says. “People come in, and it is my show. It feels like I am welcoming them into my house.”

Terrence Gore: Illness, art, and a decision to live

Terrence Gore showed artistic promise early, studying at Fleisher Art Memorial as a child. As a young man, he circumvented the traditional artist’s path, becoming a stylist, dancer, businessman, and international courier. He travelled the world with a backpack and a pair of rollerblades, delivering legal documents and seeking out cultural experiences off the tourist track.

In 2005, everything changed. He was diagnosed with HIV, then with Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy, or PML, a rare neurological condition that attacks the protective sheath around nerve cells in the brain. People with PML often die within weeks. “I lost my sight. I could not walk,” he says. “But I heard a voice clearly that said, I am going to live.”

He began teaching himself to create art with his non-dominant hand while lying in a hospital bed. Friends brought magazines so he could tear images and build collages in the spirit of Romare Bearden. Each new work was both an experiment and a lifeline.

“I had said before that if something like this ever happened to me, I would not be silent,” he says. “I would be a spokesperson. I would create a healing center. Then life put that to the test.”

Over time, he developed a body of mixed-media work that blends paint, collage, and natural materials, much of which was gathered from Bartram’s Garden. He works on multiple pieces at once, sometimes for a decade or more, returning as new stories and symbols emerge.

Terrence Gore: Back to the Garden

Most of the 10 works in “Back to My Roots” were created between 2005 and 2018. They are rich in history: Geechee and Gullah heritage, Southern family stories, Bartram Village childhood memories, and the ongoing legacy of race, religion, and survival in America.

One long horizontal work traces the path from the transatlantic slave trade through enslavement, imposed religion and racism, to Black entrepreneurship and resistance. Terrence Gore expected it to be challenging for some visitors. Instead, he has watched people from Europe, Australia, and nearby neighborhoods stand before it, tears in their eyes.

“I ask people, tell me what you see,” he says. “Tell me how it makes you feel. That is your story. That is the beauty of art. It is another voice I have.”

The exhibition itself almost did not happen. Earlier this year, Terrence Gore was again in the hospital and rehab as doctors adjusted seizure medications. At one point, he was unable to walk. Insurance pushed to cut off care. He chose to leave.

“I said, I cannot stay here,” he recalls. “I need to be around my art.”

From his bed, he worked with Bartram’s Garden staff and friends who measured the house rooms, FaceTimed him from the site, and helped him plan the layout. Once home, friends carried him up the steps into his studio so he could finish preparing the work.

By the time Bartram’s Garden’s fall events began, he was there, cane in hand, greeting visitors. Rooted in the same soil that shaped him, the exhibition unfolds as a dialogue between ecology, ancestry, and survival.

“Fifty years after that little boy was looking through the window, I am inside the house with my work,” he says. “It is such an honor.”

When the exhibition ends, the pieces will return to his studio, but Gore hopes they will not stay there for long. He imagines them in major museums and collections, in spaces where his creative story of survival can continue to teach, heal, and bear witness.

“I want people from Bartram Village to walk through those doors and feel like this is theirs too,” he says. “Because I am them, and they are me.”

Visitors will have one final chance to experience Back to My Roots on December 6, 2025, when Bartram’s Garden hosts its Winter Holiday Festival at 5400 Lindbergh Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19143.

About Post Author

Discover more from dosage MAGAZINE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.